News Detail

Politicians’ distorted perceptions

August 17, 2016 |

Politicians tend to have distorted perceptions of their opponents: not only do they overestimate the extent to which their positions differ, but they believe their adversaries to be more influential than they really are. Among political scientists, such misperceptions are known as the “devil shift”. This phenomenon can be explained by the fact that, cognitively, people find it difficult to have a positive image of their opponents, as well as feeling a need to differentiate themselves. In addition, politicians remember defeats more vividly than victories, and – in a democracy – defeats will generally be more frequent. Supposedly more successful opponents are then considered to have great influence. Thus, according to Manuel Fischer of the Environmental Social Sciences department at Eawag, “Mistrust and conflict among political actors are not only based on disagreements over substantive policy issues but also on socio-psychological mechanisms.”

The devil shift in Swiss politics

Fischer, together with his colleague Karin Ingold and researchers at Geneva University, wished to investigate whether the devil shift, as described by theorists, can actually be observed in political reality. In a project sponsored by the Swiss National Science Foundation, they analysed nine of the most important policy processes in Switzerland from the period 2001–2006. The study covered issues ranging from the introduction of the Nuclear Energy Act and the 11th reform of the state pension scheme (AHV) to the bilateral agreements on the extension of freedom of movement and on Switzerland’s participation in the Schengen/Dublin agreements. The political scientists conducted over 200 interviews with actors who had been involved in the various policy processes, including representatives from the Federal Administration, political parties, interest groups and academia. They recorded the actors’ subjective evaluations of the degree of conflict with their opponents’ positions and of their influence. These results were then compared with an objective assessment based on actual substantive policy differences and on average values derived from all actors’ estimates.

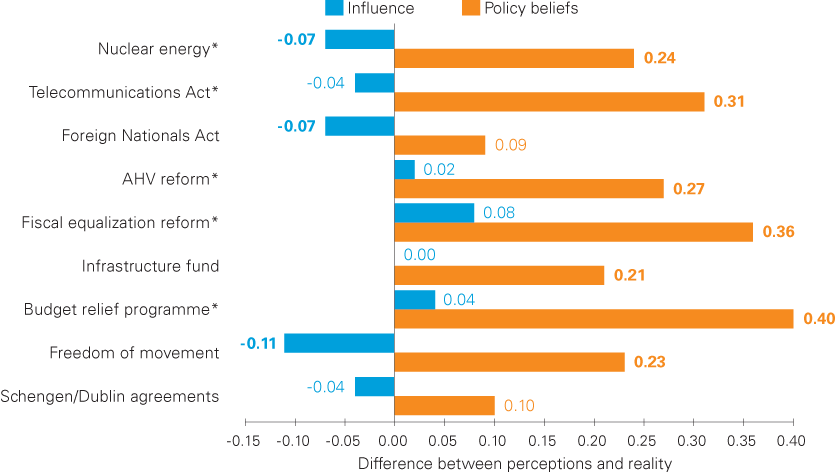

The researchers demonstrated that Swiss politics is not immune to the devil shift. Thus, political actors often overestimated the dissimilarity between their opponents’ positions and their own values and beliefs (Fig. 2). Fischer comments: “Parties, interest groups and more powerful actors in general are more affected by the devil shift than state actors and scientists.” This can be explained by more intense competition: parties seek to defend their supporters’ interests in Parliament and are dependent on their approval. Interest groups have to represent their members’ concerns and compete for financial support or even for survival. Leaders and other figures playing a prominent role are highly exposed to criticism from their opponents.

According to the study, the devil shift is particularly marked in policy processes relating to socioeconomic issues. “Here, the traditional Right-Left opposition is the main conflict line,” says Fischer: entrenched positions and ideologies defended for decades give rise to clearly defined coalition boundaries. This promotes the (mis)perception that the views of political adversaries are fundamentally opposed to one’s own. “In other areas,” says Fischer, “the boundaries between coalitions are less well established; in addition, the actors’ material interests are usually less directly affected.”

In Swiss politics, evidence for the second dimension of the devil shift – political actors’ tendency to overestimate their opponents’ influence – is less conclusive. In some cases, actors were even found to underestimate this influence (Fig. 2).

State actors’ role as mediators

What are the implications of these misperceptions for day-to-day political decision‑making? Fischer concludes: “The devil shift leads to more polarization, disagreement and mistrust among political opponents.” This, in turn, hampers cooperation across coalition boundaries, which is particularly important in consensus-based forms of government such as the Swiss system: “It impedes efficient and effective policy-making and ultimately the production of feasible compromises. Conflicts have become a more common feature of Swiss politics in recent years.”

How can the political divides be bridged? According to the authors of the study, there is a need for actors to cross the well-established borders between coalitions of parties and interest groups so as to seek solutions with political opponents. Cross-party cooperation, e.g. in committees, can help to break down barriers. State actors – less affected by the devil shift – may also play a crucial role. They are used to engaging with different political groups and taking different interests into account. In addition, as Fischer points out, they usually advocate more moderate positions than politicians or lobbyists: “This means that state actors can serve as neutral and credible mediators among competing coalitions.”

The researchers assume that the devil shift is not confined to Switzerland. On the contrary, if the phenomenon is observed in a country viewed as a paradigm case of consensus democracy, it is likely to be more pronounced in countries with a less compromise-oriented system of government.