News Detail

“We must preserve our drinking water resources”

September 4, 2025 |

Mr Berg, you have been researching water resources all over the world for decades. When it comes to water resources, people probably think first of lakes and rivers. But what is the importance of groundwater?

Groundwater is a very important topic that people tend not to consider because it is hidden underground, but it is an important basis for life. Everyone needs water every day. While a large proportion of the freshwater on our planet is bound up in ice at the poles and in glaciers, 99 percent of liquid freshwater is groundwater. Lakes and rivers contain only about one percent of the world’s liquid freshwater. When humanity discovered that it could use water from underground, this triggered a huge surge in development. Today, around half of the world’s population depends on groundwater for its basic needs.

How important is groundwater for the supply of drinking water in Switzerland?

In Switzerland, 80 percent of drinking water comes from groundwater. Half of this water is pumped from underground via wells. The other half is spring water that naturally flows to the earth’s surface. However, this spring water was still groundwater shortly before surfacing and we therefore include it in this category.

In recent years, water has become scarce in some places during summer. Should we expect water shortages in Switzerland in the future due to climate change?

Although there is no overall shortage of water here, water can become scarce in certain areas. This means that while there is a lot of groundwater, its quantity is increasingly unevenly distributed over the seasons (see article “Less water in summer, more in winter”). During the more frequent dry periods in summer, climate change can lead to localised shortages – particularly in aquifers with low storage capacity. In mountainous areas, there is sometimes little water because the lack of snow means that the springs supply less water and the aquifers also become less productive over time. Many of us still recall the images of helicopters flying water to the Alps so that herds of cows had enough to drink during a particularly dry summer.

How can we address this local shortage of water?

Various measures can be taken and it is important to choose the right one for each situation. The groundwater can be artificially recharged with river water, for example. In addition, many water suppliers are now interconnected via their distribution networks, allowing them to help each other out when necessary. However, it is not yet possible to bridge supply shortages during dry periods everywhere. In the mountains, solutions must be found for retaining and storing the water – where it is available. These solutions are not impossible, as can be seen from the large reservoirs in ski resorts that were built for the snow-making systems. But they require the political will to implement them.

The problems relating to the quantity of groundwater could therefore be solved, at least in theory. But what about the quality of these drinking water resources?

Groundwater is purified as it passes through the earth. Nevertheless, pollutants do enter the groundwater from time to time. The Federal Office for the Environment (FOEN) has had a monitoring programme in place for a long time, which has also detected the exceedance of local threshold values in the past, for example due to the herbicide atrazine. On the whole, however, we believed that our water was good and at most contained small, harmless traces of pollutants. Now it has become clear: that is not the case everywhere. This realisation is unsettling the population and challenging authorities and practitioners to act. One example is the fungicide chlorothalonil. Degradation products of this substance have been discovered in groundwater that are classified as harmful and exceed the limit value in some places (see article “Specialist in the detection of harmful substances”). In this case, the authorities reacted and banned the pesticide.

Has the problem been solved by banning the pollutant?

No, groundwater sometimes has a very long residence time of years to decades. For example, degradation products of atrazine can still be found today, even though this active ingredient was removed from the FOPH Plant Protection Products Ordinance in 2007. Some of these micropollutants also interact with the soil material and only enter the groundwater after a delay. It can therefore take a very long time for political measures to have an effect. It is therefore important to react as early as possible. After all, prevention is better than cure.

Another substance that has recently hit the headlines is trifluoroacetic acid (TFA). What’s the story with that?

In 2000, I was the lead author of a study on the mass balance of TFA in Switzerland. The substance was still very difficult to analyse at the time, but it was known that it was accumulating in the groundwater and no longer disappearing. But because it was considered harmless to health, the matter was not investigated further. Now, 25 years later, we can see that the concentrations have become very high. In addition, trifluoroacetic acid is now classified as a PFAS and therefore belongs to a class of substances that is not easily degradable. According to the FOEN, TFA is currently the most widespread artificial chemical in groundwater.

Does this mean that trifluoroacetic acid could be harmful to health?

There are currently no toxicological studies that indicate that TFA is dangerous to humans at the concentrations currently found in our bodies of water. However, this may change if concentrations continue to increase in the future. Depending on how low the threshold value is set, this could lead to problems for water suppliers. This is because TFA is a small, highly mobile ion. It is therefore difficult and expensive to eliminate it from drinking water.

What other substances pollute the groundwater?

Nitrate from fertilisers has been an issue for decades. The cantonal departments in particular are obligated to implement the applicable provisions. For a long time, nitrate was considered to be sufficiently researched. We are now applying a new approach, which we originally used in an international project to investigate the natural contamination of groundwater by arsenic and fluoride – a problem particularly in developing countries. We created maps that geostatistically predict arsenic and fluoride contamination based on a range of environmental parameters. The expertise we have acquired over the last 15 years can now be used in Switzerland to closely predict the nitrate contamination of groundwater between the existing monitoring sites and to understand why, for example, the concentration is much higher in one place than in another despite a similar area of arable land (see article “How artificial intelligence detects nitrate hotspots”).

What about the implementation of scientific findings in practice?

Of course, there are various interests and conflicts of use. Agriculture, for example, is important to us all. The agricultural sector uses chemicals in pursuit of good, high-yielding harvests, but these chemicals also find their way into the groundwater. Here, we have to find approaches that work for all stakeholders. My experience is that both agriculture and industry are very interested in finding sustainable solutions. It becomes difficult when a solution is considered too expensive. Then there are often lengthy political debates.

What is Eawag’s role in this process?

We endeavour to work together with authorities and practitioners. We also conduct basic research, some of which may only become important in practice in 20 years’ time. Yet, we don’t want to research anything that isn’t relevant. Relevance to society is extremely important to us at Eawag. For decades, our strengths have lied in the analysis of micropollutants and trace elements, among other things. Here, we develop methods that are then used in practice. With our equipment and expertise, we are undoubtedly one of the world’s leading laboratories and a valued partner in Switzerland and beyond. The transfer of knowledge and findings is also a key priority, which is why we initiated and operate the Swiss Groundwater Network (CH-GNet, see article “We want to give groundwater a face”) and the international platform GAPmaps.net. Both aim to make groundwater research visible and create a forum for exchange.

Will we still be taking most of our drinking water from groundwater in 20 years’ time?

That’s the big goal. At the moment, a large proportion of the groundwater is not even treated because its quality is so good. It is pumped out of the ground, filtered so that it no longer contains any suspended matter and fed into the network. It’s incredible. Whether this will still be possible in 20 years remains to be seen. Perhaps more municipalities will then decide to install additional water treatment facilities in order to continue to comply with the threshold values in the future. Although we are blessed with water in our country, both on the surface and underground, it is nevertheless extremely important that we are able to protect and utilise this resource in the long term.

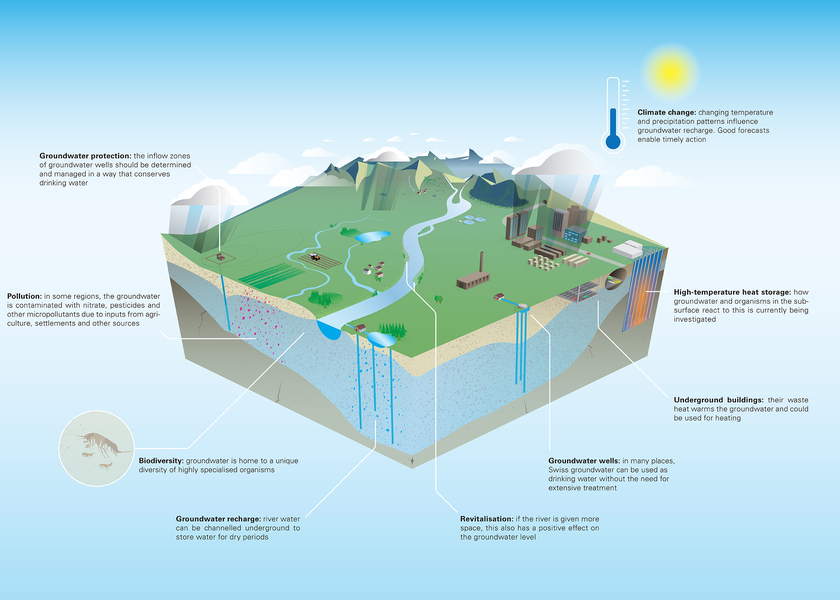

Cover picture: “Groundwater – utilising and protecting the resource drinking water” is the topic of the Eawag Info Day 2025. (Graphic: grafikvonfrauschubert, Eawag)