Improving the implementation of legal requirements

Legislation requires groundwater protection zones to protect drinking water wells from contamination. However, enforcement deficits and conflicts of use often prevent this. Parliament has therefore passed amendments to the law and other measures to ensure that groundwater can continue to be used as drinking water in the future without the need for extensive treatment.

The aim of water protection legislation is to protect water bodies and groundwater in Switzerland from adverse effects. An important instrument for the protection of drinking water is the definition of groundwater protection zones in which certain uses are prohibited or restricted. “Groundwater protection zones must be demarcated around all drinking water wells,” explains Michael Schärer, Head of the Groundwater Protection Department at the Federal Office for the Environment (FOEN). “The closer you are to a well, the greater the restrictions on property.”

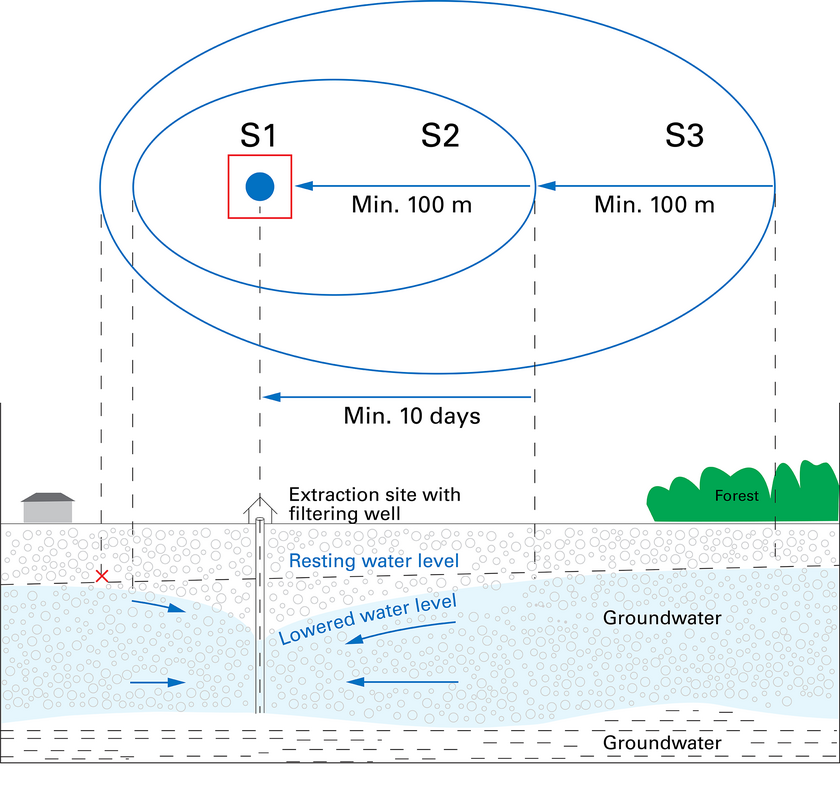

The S1 protection zone within ten metres of the well has the strictest restrictions and must be fenced off. There is a general construction ban in zone S2 and no liquid manure may be spread there. This zone is measured in such a way that the groundwater flow time from the edge of the zone to the well is at least ten days or that it extends at least 100 metres around the well. This is to ensure that pathogens and pollutants – such as heating oil – are retained or broken down in the soil before entering the drinking water supply. No fuel stations or other industrial and commercial operations that pose a risk to the groundwater may be built in zone S3, which is another 100 metres away.

In addition to these protection zones, there is another important instrument for protecting drinking water extraction sites from contamination, known as the inflow zone. This refers to the part of the catchment area of a groundwater well from which 90 percent of the water originates. This generally corresponds to 30 to 90 percent of the area of the entire catchment area of the groundwater well. In this area, measures must be taken to protect the drinking water against contamination. This instrument was included in the Water Protection Ordinance at the end of the 1990s to prevent poorly degradable and mobile pollutants, such as degradation products of pesticides, nitrate or chloride, from entering drinking water extraction sites. “If contaminants like these are present in the water extraction site, the inflow zone must be determined and measures taken to ensure that these substances are no longer discharged or released there,” explains Schärer.

Recognising and eliminating enforcement deficits

The cantons implement these regulations, while the municipalities are usually responsible for groundwater protection zones. But there are problems with these protection zones. “More and more areas are being built on, especially on the Central Plateau, and the current regulations are not being implemented in the protection zones. This puts the drinking water at risk,” says Schärer. The necessary remediation measures for older buildings in groundwater protection zones often fail to be completed due to the high costs. There is also a need for action in the inflow zones. The FOEN estimates that around 800 inflow zones throughout Switzerland need to be identified due to nitrate contamination, but only 70 have been identified so far.

Given these deficits, the National Council’s Control Committee drew up the report “Groundwater protection in Switzerland” in 2022 and formulated recommendations for the Federal Council. The Federal Council then instructed the administration to implement these recommendations. “As the supervisory authority, we are now required to exert a stronger and nationally consistent influence on the implementation of groundwater protection,” Schärer notes. In most cantons, the municipalities are responsible for designating groundwater protection zones. “To make progress here, we want to support the cantons and, above all, the municipalities more strongly in future,” he says. The FOEN has therefore initiated the groundwater protection platform at the University of Neuchâtel (see article “Groundwater protection: support in enforcement”). In collaboration with the federal government and cantons, it is now developing tools to help municipalities and water suppliers recognise and rectify problematic enforcement deficits in groundwater protection zones.

Protecting groundwater quality

Particularly on the Central Plateau, groundwater is contaminated with the nutrient nitrate and organic trace substances such as pesticides. These substances enter groundwater and surface waters from agriculture, residential areas and other sources. According to the objectives of the legislation, groundwater should fulfil the requirements for drinking water under food law following simple treatment processes. “An important principle,” Schärer explains, “is that the groundwater can be used directly as drinking water wherever possible.” Simple treatment processes include filtration to remove suspended particles and treatment with UV light to kill pathogens.

In fact, the quality of the groundwater in the majority of Switzerland’s 12,000 groundwater wells is so good that it can be used as drinking water without the need for extensive treatment. If the groundwater had to undergo further treatment, drinking water charges would be up to around 50 percent higher. “Extensive technical treatment is not a solution for Switzerland’s decentralised water supply,” says Schärer. This would inevitably lead to a strong centralisation of the drinking water supply, which is currently decentralised and less susceptible to disruption. This would make the supply of drinking water in Switzerland more difficult, especially in view of climate change with longer dry periods.

Several legislative amendments initiated

In order to continue ensuring the quality of groundwater in the future, the Swiss parliament passed a legislative package in 2021 to reduce the risk of pesticides in bodies of water. This was in response to the widespread contamination of groundwater with degradation products of the pesticide chlorothalonil and the popular initiatives “For clean drinking water and healthy food” and “For a Switzerland without synthetic pesticides”.

The legislative package includes various measures. Among other things, no plant protection products that lead to concentrations of active substances or degradation products of more than 0.1 micrograms per litre in groundwater may be used in the inflow zone of drinking water extraction sites.

To ensure that this restriction can also be implemented, a further amendment to the law is being prepared in implementation of Motion 20.3625 “Effective drinking water protection by determining the inflow zones”. This is intended to make sure that the cantons throughout Switzerland actually determine the required inflow zones within the set deadlines. “Ultimately, it is important that any activities in the inflow zones take place with due consideration of the drinking water supply,” explains Schärer.

Preparing for dry periods

In view of climate change and reduced precipitation in summer, the FOEN was also commissioned to prepare a report after longer and more pronounced dry periods. “The aim is for the federal government to identify where problems or conflicts arise during dry periods that cannot be solved with existing measures,” explains Schärer. Parliament has also instructed the FOEN to draw up a strategy on “Water management – dry periods, heavy precipitation, quality of water supply and protection of aquatic habitats” with recommendations for the cantons. “Anticipatory planning is intended to avoid conflicts by clarifying who is authorised to use the groundwater and when,” says Schärer.

The protection of groundwater is of central importance to secure the supply of drinking water in Switzerland for future generations. The challenges are manifold: enforcement difficulties, conflicts of use and climate change. “The necessary solutions are in the works or already exist and must now be implemented,” concludes Schärer. “This should be possible in a Switzerland known as 'the water tower of Europe'.”

Created by Barbara Vonarburg for the Info Day Magazine 2025