Department Sanitation, Water and Solid Waste for Development

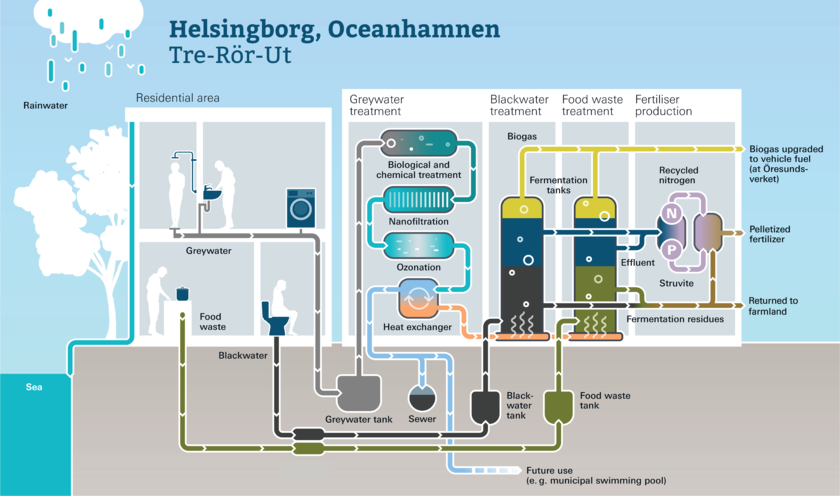

Figure 1: Schematic overview of the ‘Tre-Rör-Ut’ system implemented in Helsingborg, Sweden. The system recovers biogas for vehicle fuel, nutrients for fertiliser production, concentrated sludge for agricultural application, and greywater for reuse water (own illustration based on https://www.recolab.se/utvecklingsanlaggning/).

Decentralised urban (waste)water treatment and reuse systems improve the flexibility, resilience and sustainability of water and sanitation infrastructure and are, thus, a key component of urban sustainability transitions. The Lighthouse Project assessed some of the most prominent examples from around the world.

Why? – Project Goals

Urban water and wastewater management needs to be deeply transformed, away from end-of-pipe to circular designs. Actors around the world have started developing decentralised urban water treatment and reuse systems (DUWTRS). DUWTRS locally treat and recycle water and the resources it contains (heat, energy, nutrients) in closed-loop systems. They increasingly include source-separation, i.e. divide various ‘waste flows’ such as greywater, blackwater, rainwater or kitchen waste and convey them to separate treatment processes (cf. Figure 1). This promises efficient treatment and targeted resource recovery.

Yet, in solving multiple challenges at once, DUWTRS typically transcend traditional institutional and regulative boundaries between the waste, water and energy sectors, as well as between the public and private sphere. In effect, only a few cities worldwide have successfully implemented innovative approaches at scale. We lack well-documented templates and best practices that inspire and inform on how to best implement DUWTRS. Thus, the Lighthouse Project (LH) assessed key case studies, which could serve as ‘templates’ that inspire other cities around the world.

What? – How do we define Lighthouse Initiatives?

- Comprehensive socio-technical configuration that integrates new technologies into a matching socio-economic and institutional context.

- Long-term perspective in terms of project length and available funding, creating a stable incentive / support structure, enabling ‘adaptive learning’ among local actors.

- Broad-scale adoption, at the minimum for a neighbourhood or city district level (fully developed value chain comparable with the fully mature, centralized approach).

- Visibility and impact beyond immediate context, that it can inspire and guide similar initiatives looking to replicate its core features.

Where & When? – Selected Case Studies

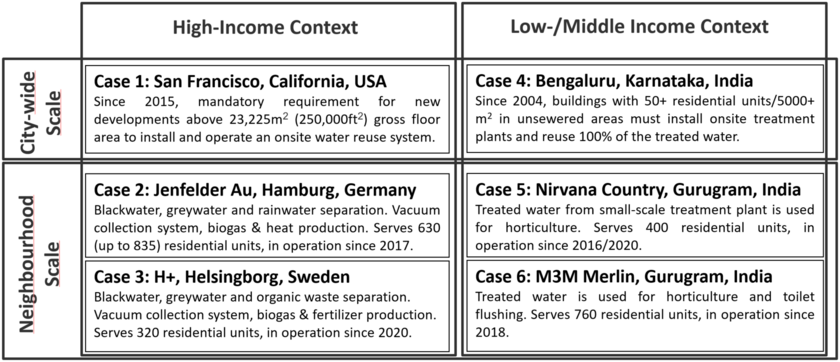

To generate practice-oriented lessons, we compared six projects at different scales (city-wide vs. neighbourhood), in different contexts (high-income vs. middle-income) and using different technological set-ups. We defined five sample criteria for potential LH initiatives (must reflect all four LH characteristics; Operate a DUWTRS including resource recovery (e.g. water, energy, heat, nutrients,…); Dispose of a fully developed service chain from collection to disposal/reuse; Serve a minimum of 300 residential units; Be in operation for min. 2 years.) and finally selected four neighbourhood-scale and two city-scale projects, equally distributed across high- and middle-income contexts (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Overview on selected and assessed lighthouse initiatives

Data was collected in two related research projects at Eawag (4S and BARRIERS), as well as with targeted follow-up fieldwork campaigns between November 2021 and August 2022 including extensive literature reviews and semi-structured key-informant interviews. Interviewees were selected from relevant stakeholder groups - on average, 20 interviews were conducted per case, which resulted in more than 100 interviews informing the data analysis. We developed and applied an integrative assessment framework and used qualitative analysis tools to structure success conditions for implementing and operating DUWTRS.

Results

Innovative DUWTRS solutions are a systemic, cross-sectoral innovation that not only challenges established infrastructure itself but also the manner in which it is currently planned, operated and maintained. Our case studies expose three generic models of DUWTRS implementation:

- A policy-induced and networked/market-based model as exemplified by San Francisco and Bengaluru. These cases arguably represent the most transformative model. With relatively small, onsite DUWTRS systems implemented city-wide, they shift key responsibilities from public service providers (utilities) to private entities (developers, firms, owners, residents). In this model, private actors plan, implement, operate and maintain DUWTRS, which are permitted, (indirectly) supervised and sanctioned by public authorities. The role of the utility shifts from full-fledged top-down control to network facilitation and system intermediation.

- Neighbourhood-scale solutions such as Hamburg and Helsingborg with advanced resource recovery systems follow a more conventional model, where a public utility largely covers water and sanitation services, occasionally complemented with private sector involvement if and where regulations allow or require. Yet, as our case studies vividly illustrate, this model typically also transcends the traditional institutional and regulatory boundaries between the waste, water and energy sectors, as well as between public and private spheres and thus still ask for substantive innovation and transformation in the affected utilities and related stakeholder groups.

- Gurugram illustrates that manifold hybrid models in-between these two ideal-types may exist, in which a DUWTRS solution is installed at a district scale, but still mostly managed by private actors and the local RWA’s. Many similar ‘hybrid’ solutions can be envisioned in this in-between space of ‘distributed’ or ‘cluster’ solutions.

10 key ingredients for successful implementation of decentralised urban water treatment and reuse systems (DUWTRS)

To distil the most general and practical ingredients needed for successfully implementing innovative DUWTRS solutions, 10 key ingredients of a successful DUWTRS recipe can be identified.

- A dedicated system integrator that coordinates and aligns a large number of stakeholders with varying interests

No matter the DUWTRS type, main drivers, or income levels, coordinating a large number of different stakeholder groups, such as regulators, utilities, planners, architects, developers, builders, service companies, researchers and end-users is indispensable. Having a ‘champion’ or system intermediary is key for identifying potential synergies between interests, mitigating conflicting worldviews and creating long-term strategic guidance. As successful DUWTRS implementation usually takes 10 or more years, this particular actor type must be willing to engage in a gradual and collective learning process that moves through several iterations. - A dense and transdisciplinary stakeholder network, which participatively creates solutions that transcend boundaries between sectors (water, sanitation, energy,…) and between public and private spheres

The involved stakeholders need to be pro-actively connected through arenas and events that allow for open, interactive and constructive formal and informal exchanges. Relevant stakeholders need to be actively identified and the networks between them strategically nurtured on a regular basis. Sustained networking coupled with a participative approach helps creating a collaborative and cooperative atmosphere and establishing a common vision, all of which are crucial for stabilizing the DUWTRS implementation path. An interactive and reflexive approach furthermore helps to distribute ownership, which increases overall legitimacy. - Stable political and policy support including allocation of adequate human and financial resources

Given the long implementation timeframes, DUWTRS need stable support by relevant policy circles. A long-term policy programme – or at least concise and long-term policy support – drastically increases the chances to successfully establishing a DUWTRS configuration ‘that works’ and legitimising it beyond early adopters. Most importantly, policy support should go hand in hand with budget allocations that endow the key system integrators with sufficient (financial, organisational and human) resources to effectively perform their leading role. - Legal and regulatory arrangements that are adapted to DUWTRS’s specific requirements

DUWTRS implementation is confronted with major legal and regulatory barriers. In all cases, local actors had to actively engage in regulative change processes or smartly adapt their technology solutions to operate them on a sound legal basis. DUWTRS typically rely on a broad variety of source waters (rainwater, greywater, blackwater, A/C condensate, etc.), which can be used for different indoor and outdoor reuse options (toilet flushing, washing machines, irrigation, cooling, etc.). They thus inherently ask for a ‘fit-for-purpose’ regulatory approach, which aligns water quality standards and O&M procedures with specific combinations of water sources and reuse purposes. - A well-defined permitting pathway, water quality monitoring and enforcement system

Legal and regulatory frameworks only lead to sustainable outcomes if it they are combined with an effective approval procedure that clearly outlines the roles and responsibilities of all involved authorities, effective quality monitoring approaches, as well as potent enforcement and sanction mechanisms. Concerning enforcement, a well-defined vetting process for design and construction quality, remote quality monitoring processes and a lead-authority equipped with adequate human and financial resources to conduct spot-checks are key. - Attractive business models and markets for the products generated in DUWTRS

DUWTRS offer a unique opportunity to turn sanitation from a ‘waste management’ problem into a business opportunity. The water and the resources (heat, energy, nutrients) can effectively be turned into marketable products, which create economic, environmental and social co-benefits. Reaping those is only possible if functional markets for end products exist and related business models are developed. A design-build-operate business model that makes the same firm responsible for all parts of the DUWTRS implementation cycle entails strong incentives to design well-adapted systems and to increase regulatory compliance, robustness, longevity, and, ultimately, economic viability. - Industry-internal standards and norms, certified training systems and information materials

Industry-internal standardisation, certified trainings and information sharing are key to success. Decentralised markets for DUWTRS hamper knowledge diffusion and quality monitoring among competitors and insufficient industry standardisation can lead to a proliferation of untrustworthy technology suppliers and service providers.- Having widely shared quality vetting, standardisation and quality labelling processes in place are key for creating mature markets and an industry that meets performance (and thus environmental and public health) standards and enables standardised, compatible system components, whereas certification of vendors and suppliers increases transparency and fosters accountability across the service chain.

- Certified training systems allow establishing and sharing state-of-the-art knowledge, skills and capacities across planners, installers and operators of DUWTRS solutions, which are best delivered in collaboration with (main) technical suppliers and organised by an industry association.

- Well-designed information and training materials tailored to key target groups that are known, accessible and comprehensible are crucial to guarantee a smooth knowledge transfer and training process. Detailed information is often available, but does not trickle down to those responsible e.g. for DUWTRS planning or construction. This requires a knowledge dissemination strategy, for which national professional associations could serve as promoters and as a platform.

- An active communication and public outreach strategy that fosters legitimacy

Given the ‘yuck factor’ connected to wastewater in cultures around the world, creating legitimacy for DUWTRS is not an easy task. Thus, legitimacy for DUWTRS need to be actively and strategically created. Core storylines need to be developed that embed DUWTRS in pre-existing societal norms and make its benefits easily understandable to broad audiences. The communicative focus can lay on DUWTRS’s manifold ecological, social, economic and/or technical co-benefits. Apart from general outreach and communication campaigns, also more targeted interventions can be highly effective such as e.g. guided tours to PDPs as well as client consultations for real estate developers and future owners/residents. - Pilot- and demonstration projects enabling technology development, public outreach and exchange between LHs

Publicly accessible PDPs played a key role for technology development and legitimation. PDPs induced interdisciplinary research, through which vital technology and system knowledge was generated, which in turn increased trust within the utility and with city officials. Simultaneously, they serve as an accessible and tangible ‘proof of concept’, and thus as a legitimising object for developers, owners and (future) residents. - Long-time economic and financial viability (in a full system and infrastructure lifecycle perspective)

A key challenge for DUWTRS are their (still) comparably high CAPEX and OPEX, especially when compared to conventional (and often highly subsidised) centralised solutions. Finding financially and economically viable system designs is thus a key task for any city implementing DUWTRS. At the same time, comparisons with centralised infrastructure should be based on a full system and comprehensive environmental life cycle assessment. Especially district-scale solutions usually achieve high sustainability impacts with very reasonable additional costs. In middle-income contexts, freshwater prices tend to fluctuate strongly and centralised infrastructure usually performs rather poorly, thus making also city-wide DUWTRS economically and environmentally highly attractive. This notwithstanding, it is important that investments into DUWTRS pay-off for investors, end-users and the environment in the long term.