News Detail

10 years of Eawag Sensorlab

November 11, 2025 |

Discussion led by Jörg Rieckermann, text edited by Andri Bryner

Since 2015, the Sensorlab has been a cross-departmental resource at Eawag. Its full name is Laboratory for Sensor Networks, Automation and Electronics. It supports researchers in the development, adaptation and operation of sensors – from the initial idea and prototypes to data points and long-term monitoring solutions. In this way, the Sensorlab promotes interdisciplinary collaboration, both at Eawag and with external partners, and ensures that new measurement technologies can be successfully applied in research and practice.

Eawag has traditionally been strong in measurement – but where did the idea for the Sensorlab come from?

Bernhard Wehrli (BW): I came to Kastanienbaum as a chemist in the late 1980s. The physicists had oceanographic instruments, went out onto the lake, lowered the probes and had tens of thousands of data points by the evening. We chemists calibrated devices, took samples, typed data into Excel spreadsheets – and ended up with 10 or 20 measurements. That frustrated me (and made me a little jealous). Scientifically, I was inspired by Werner Simons' ion-selective electrodes: "With these, we could measure ammonium, pH and nitrate directly." In the 1990s, we therefore built the first submersible solutions with scientist Beat Müller and technician Christian Dinkel – but much of it was homemade. Later, with the Competence Centre Environment and Sustainability in the ETH domain and the IoT discussions, colleagues raved about their sensor networks, e.g. in the mountains. We saw that field measurement technology with data transfer was feasible, but our data handling was archaic. So we needed someone to set it up professionally, preferably at the Dübendorf site, so that they could get the community on board there too – moving away from lone wolves to a network of teams interested in sensors. The particle laboratory in the engineering department served as a model: open, competent, usable throughout the institute. We wanted something like that for sensor technology. Carsten Schubert, head of the Surface Water Department, quickly found other interested parties – and it worked.

Christian, you were there from the beginning – was it a big adventure or just a new job for you as a sensor specialist?

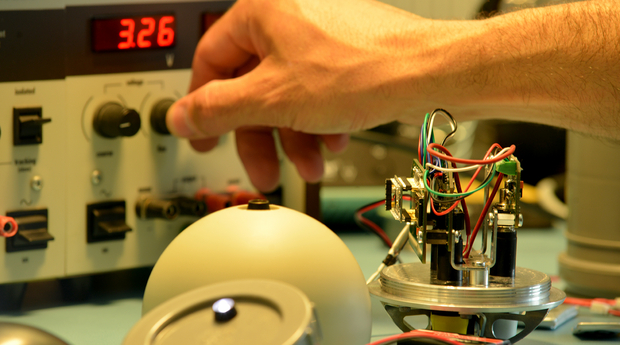

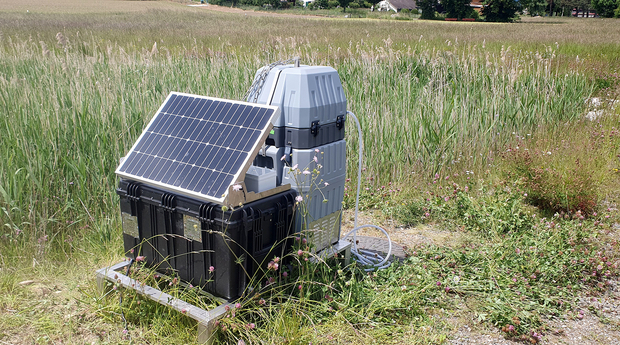

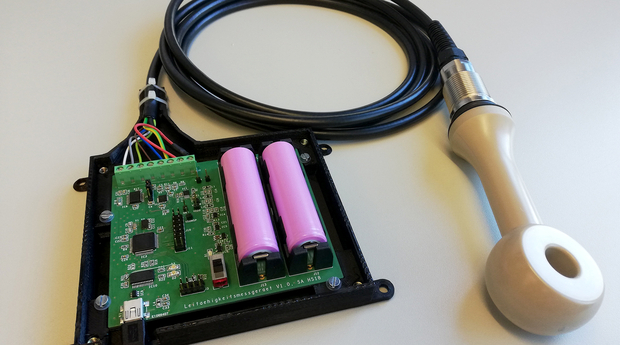

Christian Ebi (CE): I was looking for something that would satisfy me professionally and combine my interests in the environment and electronics. The position appealed to me immediately, partly because of the field measurements. The change from industry was exciting, and the atmosphere at Eawag was very positive. First, I had to understand exactly what was expected of me and translate the "language" of water researchers for myself. I quickly got started in practice by working with Francesco Pomati and on the Greifensee platform (stabilising the flow cytometer, data integration and radio transmission) and, at the same time, at SWW's Urban Water Observatory (UWO) with Frank Blumensaat (IoT sensors, low-power electronics, etc.). At the UWO, the focus was more on radio technology, and our experience with Cave-Link was invaluable there; in 2015, IoT was still in its infancy. The devices had SIM cards and data transmission was expensive. There was a lot of evaluation and networking, internally and especially with sensor technology colleagues at the universities of applied sciences, who contributed the necessary know-how for our ideas with low-energy radio.

The Sensorlab has grown steadily. Martin Breitenstein, an automation engineer, joined us, followed later by Ingo Maindorfer, a computer scientist – because there was a need to catch up in the areas of test facilities and data management. Many colleagues from other departments are helping out, such as Christian Dinkel, Simon Bloem, Alba Gutierrez and Michi Plüss. Does this still correspond to your original vision?

BW: When I hear the term "data management," I almost feel old. I come from the "very data poor world": one clever idea, 10 data points – one paper. In isotope science at Caltech, 4–7 points were sometimes enough for groundbreaking results. Today, we work in a data-rich world – which is great, but challenging. I congratulate you on this expansion.

„Being out there – in the mountains, in the sewers or on the lake – that's what makes working at Eawag unique.“ – Christian Ebi

CE: We have learned that it is not just the data points that are important, but also automation, software and mechatronics. Thanks to initiatives by Max Maurer, Christoph Ort and you, Jörg, we are now much more broadly positioned with the new appointments. Other departments are also contributing to this, for example with Marta Reyes (Eco), James Runnals (Surf) and Christian Förster (IT). We support research at NEST, for test facilities in the hall and in the field, and organise knowledge transfer with events such as sensors@eawag, Python workshops and the PEAK course on modern measurement networks.

In the beginning, it wasn't just equipment and automation know-how that was lacking, but also laboratory space. Where to put the soldering fumes? How do we protect the electronics from electrostatic discharge?

CE: Since last year, we finally have an electronics lab. That's very helpful. Sure, we improvised a lot at first, but that's okay. As requirements increased, however, space became scarce. We then spread out, including in the old pavilion, but during the Covid period, movement between the buildings was restricted; the equipment moved back to the office – and it became really cramped. With the renovation of the laboratory building, we were given a space in the C wing just in time for our 10th anniversary, thanks to the efforts of Heinz Singer and Christoph Ort. We have been in the new laboratory since May: we have good lighting, antistatic flooring and suitable furniture. Now we can also safely maintain valuable electronics such as the Aquascope. This makes a huge difference to quality and efficiency.

10 years of Sensorlab – what are the highlights from your point of view?

CE: What excites me most is the combination with field work. Whether in the mountains, in the sewers or on the lake: the connection between technology and nature is always something special. Our role is always supportive – the ideas for the projects come from the research departments. And without the other technicians and the workshop, nothing would work anyway. But being out there is what makes working at Eawag unique for me. And the moments when you feel genuine gratitude are particularly wonderful – that's incredibly motivating.

BW: For me, it's a highlight that we've been able to realise ideas from environmental research and thus be part of the rapid developments in sensor technology, data acquisition and storage. Without the Sensorlab, we would probably have been left behind.

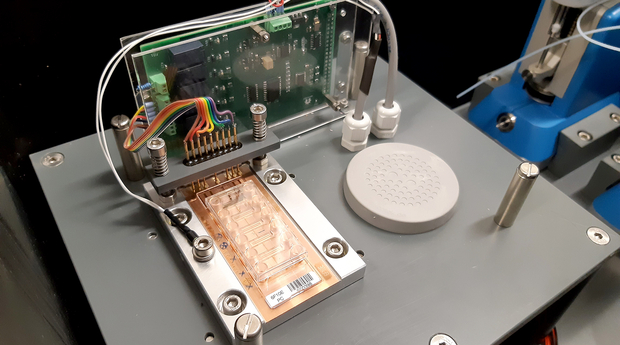

Jörg Rieckermann (JR): I would also like to mention the "Sewer Ball" (aka SQUID). Together with a postdoc in Christoph Ort's group, we developed a floating sensor for the sewer system that measures changes in temperature and conductivity in the flowing wave.

SUEZ then further developed the open hardware sensor platform with the postdoc's company and now offers global services with it. They use it to detect seawater ingress into the sewer system, for example, which we would never have thought of. A real success story to which the Sensorlab contributed (see also video).

Were there or are there any setbacks or shortcomings?

CE: A project with the four research institutes on cooperation in the field of sensors was actually a highlight – we were able to network a lot and gain insights into other areas. But in the end, it turned out that the concrete interest was rather one-sided and only supported by a few. I was a little disappointed that the spirit of cooperation is obviously not as widespread everywhere as it is here.

„I hope for an ‘Argo’ network for fresh water – with sensors that automatically measure and transmit data worldwide.“ – Bernhard Wehrli

BW: Yes, I can only confirm the stumbling blocks of interdisciplinary collaboration. I have often tried to initiate collaborative projects. It was good when young people came together – there was a lot of enthusiasm. But because the managers looked after their own group first, it also took postdocs to support such projects. Interdisciplinary collaboration is demanding, it costs more than a single project and often produces fewer papers. But it can be more original and exclusive – and we must not give up this interdisciplinary strength. It is the hallmark of Eawag.

What will the next 10 years bring?

CE: In ten years, field measurements will certainly still be needed. But the issues may change, shifting more towards water quality – perhaps biological sensors will become more important for monitoring health aspects in water. I would also like to see us become more sustainable in terms of hardware: in today's IoT world, far too many batteries are needed, and the sensors available for purchase, some of which are far too cheap, are of poor quality. We need more durable and resource-efficient solutions.

JR: Yes, exactly: autonomous sensors with energy harvesting instead of batteries. I also envisage user-friendly databases that not only store figures, but also the engineering knowledge behind them – so that in future you can query the data directly to find out where the sewage system is at full capacity or where the largest groundwater intrusions are.

BW: I hope for an "Argo" network for fresh water, similar to the one that oceanography has had for 25 years – with sensors that automatically measure and transmit data. It is almost scandalous that such an international measurement network for rivers and lakes has not been implemented for political reasons, even though the environment is changing so dramatically. Technically, this would be easily achievable today. Eawag should provide inspiration and help to establish such a global network for sustainable monitoring.

Cover picture: A series of temperature sensors with radio transmission is ready for a general overhaul, as operating conditions in the mountains or in sewer systems can be harsh. (Andri Bryner, Eawag)