News Detail

Plastic pollution: From Phu Yen to a global solution

January 12, 2026 |

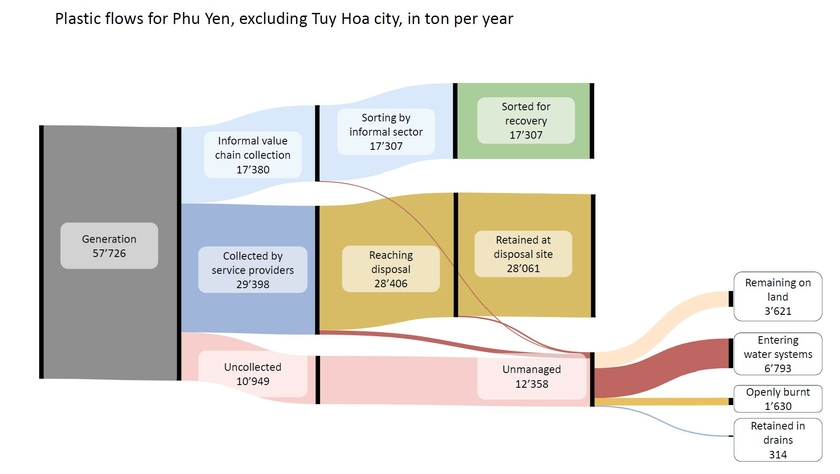

To track the flows of plastic waste from sources to their fates, the Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology Eawag, in collaboration with international partners, developed a tool around 5 years ago: The Waste Flow Diagram (WFD) makes it possible to map plastic waste flows throughout the entire solid waste management service chain and to identify where and why plastics leak from the system into the environment. This provides a practical method for identifying areas where improvements in waste management are needed.

A new study by Eawag has now applied the WFD at the provincial level for the first time. “This is a methodological milestone,” explains Dorian Tosi Robinson, researcher in Eawag’s Department Sanitation, Water and Solid Waste for Development (Sandec) and lead author of the study. “Until now, the tool has only been used for individual cities, not for entire regions. This expansion makes it possible to systematically record plastic waste across larger areas and also include rural areas and smaller towns.”

The results from Phu Yen show that 9.4 kilograms of plastic waste per capita ends up in waterways there every year. However, this figure only applies to rural and smaller urban areas in the province; the capital, Tuy Hoa City, was not included in this calculation. It is particularly striking that 88.6 per cent of this plastic waste comes from uncollected waste, meaning plastic that ends up directly in the environment in areas without a functioning waste collection system. Other sources include waste collection and transport (approximately 8 per cent), landfills and disposal facilities (approximately 3 per cent), and the informal sector (0.6 per cent), which collects recyclables for resale on the secondary market.

Major regional differences

The study clearly shows that the situation varies greatly from district to district. While some districts see only one kilogram of plastic per capita per year entering waterways, others reach over 55 kilograms: more than fifty times as much.Despite these enormous differences, a common pattern emerges: In nearly all districts, the majority of pollution originates from uncollected waste. Expanding waste collection is therefore a top priority everywhere, but the specific implementation must be tailored to local conditions.

Calculating plastic waste

The study tested two methods to calculate how much plastic ends up in the environment in a region: the sum method and the weighted method. Both methods used the waste flow diagram. Experts on site observe how waste is collected, transported, recycled or disposed of and use defined categories to estimate how much plastic is leaked in the process. This includes, for example, plastic waste that is not collected.

- In the sum method, a separate diagram is created for each district and the results are then added together. This shows regional differences particularly well and proved to be practical to implement.

- The weighted method creates only a single diagram for the entire province and uses average values. It was intended to simplify the presentation, but proved to be less effective: not only did the method lose detail, but it was also more complex to use than hoped.

Both methods deliver similar overall results, but the sum method is significantly more accurate at the local level. It is also easier to implement, even though it requires more individual analyses. However, the researchers also emphasise the limitations of their work: for even more accurate results, waste audits would have been necessary in each individual district. This would have required an effort that far exceeded the available resources. Instead, they mainly used existing data, field observations and estimates. Despite these limitations, the results are robust enough to derive concrete recommendations for action.

Intervening at the source

The study shows that the Waste Flow Diagram can be successfully applied to larger administrative units. Despite the larger area and more complex data sets, the WFD delivers consistent results that enable concrete recommendations for action. However, the researchers emphasise that accurate data alone is not enough. It is crucial that countries, provinces and local governments take responsibility for their contribution to aquatic and marine pollution. Only then can behaviour be changed and administrative structures improved.

This is precisely where the strength of the WFD lies: it not only shows how much plastic enters the environment, but also where exactly and why. This transparency creates accountability and enables targeted interventions where they are most effective: at the source, before plastic even enters water systems and the sea. Once in the ocean, plastic waste is difficult to trace back to specific sources and is hard to collect. Preventive measures are therefore not only more effective, but also more cost-effective than subsequent clean-up operations.

“With these findings, the application of the Waste Flow Diagram not only provides valuable data for Phu Yen Province, but also offers a promising basis for use in other regions,” explains Dorian Tosi Robinson. “The potential for systematically recording and sustainably reducing plastic waste worldwide is enormous and could make a decisive contribution to combating global plastic pollution.”

Original publication

Cover picture: A landfill site in Vietnam (Photo: Dorian Tosi Robinson, Eawag)

Funding / Collaborations

- Eawag

- Vietnam National Foundation for Science and Technology Development (NAFOSTED)

- Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF)