Frequently asked questions about cyanobacteria

Why do we hear regularily about dogs dying?

Animals, especially dogs, are much more likely to be poisoned than humans because they drink large amounts of water at the shore (where the concentration of cyanobacteria is generally higher) and lick their fur after swimming, which may have accumulated cyanobacteria. Dogs play and bath in the water even in colder temperatures, when humans usually do not go swimming yet. Due to their higher water intake, comparatively low body weight and the fact that they do not avoid algae and do not prefer clear water like humans, dogs are particularly at risk. Unfortunately, the first sign of the presence of a cyanobacterial bloom is often a sick dog that has swum in calm or stagnant water, or a sick cow that has drunk water from a pond with a bloom.

Who can I contact if I have specific questions about the situation in my region or a possible case of poisoning?

Contact the cantonal laboratory, the water protection authority in your canton or municipality of residence. For questions relating to «water in contact with the human body», see also the website of the Federal Food Safety and Veterinary Office.

What promotes the mass proliferation (bloom) of cyanobacteria?

Mass proliferation (blooms) of cyanobacteria in the open water column requires calm, warm water, sufficient sunlight and nutrients (nitrogen and phosphorus). If conditions are right, blooms can form within days or weeks.

Some cyanobacteria have gas bubbles in their cells, which they use to regulate their buoyancy like submarines. In summer, they can sink into the stable water column to access nutrients and then rise back to the top layer of water to use light for biomass production (photosynthesis). Their tolerance to high temperatures and high or low light levels, combined with the unique ability of some species to utilise atmospheric nitrogen, makes them almost unrivalled there. Large colonies and the production of toxins can further promote mass reproduction, as this allows the cyanobacteria to escape herbivorous zooplankton. Important to know: Other types of algae can also multiply rapidly under suitable conditions and cause significant cloudiness in the water column. Streaks or foam formation on the surface can also be caused by the decomposition of organic material by other bacteria and fungi.

Although conditions are more favourable for blooms in late summer, interactions between environmental conditions and species-specific behaviour lead to large seasonal and annual fluctuations in cyanobacterial abundance. Some toxic strains may appear already in the early summer season, while others are only found in late summer/earl autumn or winter/spring.

Should we expect more cyanobacterial blooms in the future?

Numerous studies indicate that global warming, eutrophication (overfertilisation), rising CO2 levels and changes in lake hydrology can increase the frequency, intensity and duration of cyanobacterial blooms in many aquatic ecosystems worldwide. However, the mechanisms that drive cyanobacterial blooms remain a research question with no definitive answer. For example, there are three hypotheses as to why sporadic blooms also occur in lakes that are not nutrient-rich:

- a random event leads to a nutrient spike (inflows from land, turbulent mixing);

- zooplankton selectively eats species, causing less edible cyanobacteria to accumulate; and

- wind drives the floating biomass to certain locations and concentrates it near the shore. The most important factors are likely to vary from lake to lake, and in most cases, a combination of all three factors is likely to trigger a bloom.

Rising temperatures can promote cyanobacteria directly and indirectly: warmer water can increase the growth rates of cyanobacteria (and thus the total biomass). An increase in surface water temperature can also affect cyanobacterial blooms by altering the density and physical structure of lake water. For example, lakes are becoming increasingly poorly mixed because warmer, lighter surface water does not sink to the bottom during mild winters. Cyanobacteria therefore benefit from the longer-lasting summer conditions that promote their growth and from the lack of deep-water mixing, which prevents them from sinking and decomposing at the bottom of the lake.

An Eawag study in Switzerland found that cyanobacteria have become increasingly common in lakes around the Alps over the past 100 years. The study also showed that the composition of the cyanobacteria community has become increasingly similar in all lakes, regardless of their geographical location. The main beneficiaries of ongoing global warming and the temporary nutrient surplus of the late 20th century are species that are better adapted to calm waters, some of which are potentially toxic. As a result, almost all lakes, not just a few, are now at risk of sporadic blooms. A 2017 study predicts that in the United States, the average number of days with harmful cyanobacterial blooms per water body will increase from about 7 days per year to 18-39 days in 2090.

What are the implications for the ecosystem?

Cyanobacterial blooms are not normally edible for herbivorous plankton, as the agglomerates of cells are too large and do not represent an attractive source of nutrients. They therefore do not contribute significantly to the productivity of the entire food chain (i.e., fish stocks). After a cyanobacterial bloom dies off, large quantities of organic matter sink to the lakebed, where they are decomposed by bacteria. This leads to an oxygen deficit in deeper water layers, which has two negative consequences: More nutrients are released from the sediments (which promotes growth of plankton overall and cyanobacteria), and fish are less able to live or spawn in deep water where oxygen is too low.

Which toxins are produced by cyanobacteria?

The toxins and other bioactive compounds produced by cyanobacteria are a diverse group of chemical substances that are categorised according to their specific toxic effects, including:

- Neurotoxins affect the nervous system.

- Hepatotoxins affect the liver.

- Tumour promoters are chemicals that can increase tumour growth with chronic exposure.

- Lipopolysaccharides are chemicals that can affect the gastrointestinal tract and the immune system.

- Enzyme inhibitors are chemicals that prevent enzymes from performing their function, thereby disrupting metabolism or other processes.

Cyanobacteria usually produce not just one toxin, but a whole range of bioactive substances that then act together on the ecosystem.

Who controls the bathing water?

Local authorities, i.e. cantons or municipalities, are responsible for the water quality of lakes and rivers and provide information to the public on their own websites. In most cases, this information is provided by the cantonal laboratories for food inspection and consumer protection or, in some cantons, by the laboratories of the water protection agencies.

The Federal Office for the Environment (FOEN) collects cantonal data and makes it available for national reports. According to the Federal Water Protection Ordinance, the water quality of surface waters must be such that «the hygienic conditions for bathing are guaranteed where this is expressly permitted by the authorities or where a large number of people usually bathe and the authorities do not advise against it» (GSchV, Annex 2, Art. 11, 1e). The investigations are mostly based on measurements of faecal indicators such as E. coli or enterococci, which indicate contamination from domestic wastewater or fertiliser. If necessary, the local authorities issue warnings, recommendations for behaviour, instructions, or even bathing bans.

Can cyanobacteria also get into drinking water?

If possible, the location of the extraction points in deeper water layers is intended to prevent summer cyanobacterial blooms from entering the drinking water from the surface when lake water is used as drinking water. However, when the lake is mixed (usually in winter), cyanobacteria can also reach deeper water depths and enter the treatment plants with the raw water. Water supply companies therefore monitor the raw water closely to prevent cyanotoxins from entering the drinking water supply.

At what quantities do cyanbacteria become dangerous?

Several countries have established guidelines for cyanobacteria in water. It is important to note that different limits have been set for drinking water and recreational waters. Most countries use the guidelines of the World Health Organisation (WHO), including Switzerland. These guidelines focus on cyanobacterial cell counts and cyanobacterial toxin concentrations.

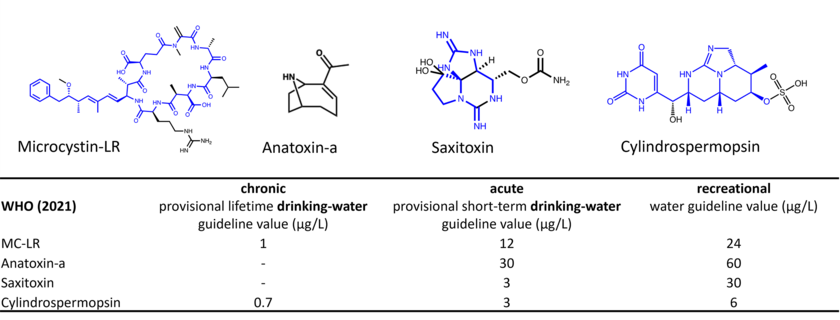

Since 2021, a total of four substances that have been sufficiently studied are listed as toxins in the WHO guidelines: microcystin-LR, which is hepatotoxic; saxitoxin and anatoxin-a, both of which are neurotoxic; and the cytotoxic cylindrospermopsin.

The most widely studied toxin for a long time was microcystin-LR, from the microcystin group (produced, for example, by Microcystis aeruginosa). The concentration of microcystins is therefore used in many countries to assess bathing water quality. Microcystins are hepatotoxins, but they are also suspected of having neurotoxic effects.

In its guidelines, the WHO classifies three risk categories based on the cell count per water volume and visibility depth:

Monitoring level | Health risk | Cyanobacteria cell count per mL | Visibility depth | Possible symptoms |

Bathing water | Barely | < 20 000 | >2 (clear) |

|

Risk Level 1: | Low | 20 000 | 1-2 (cloudy) | skin irritation, gastrointestinal illness |

Risk Level 2: | Moderate | 100 000 | 0.5-1 (streaks on the surface) | + potential long term illness |

Risk Level 3: | High | 10-100 million | <0.5 (algae carpet, green suspension) | + acute poisoning |

In addition to cell counts, the WHO also proposes limit values for toxins in drinking and bathing water.

However, cyanobacteria produce many other bioactive substances. By 2024, more than 3,000 substances specific to cyanobacteria had been identified. These include around 300 different microcystins, which are very similar in toxicity to microcystin-LR from the WHO guidelines, but differ slightly in their chemical structure. Research into most of these compounds, and beyond microcystins, is still in its infancy. There are no guidelines yet, but there are clear indications that some of these other substances disrupt biological processes and thus also pose risks to humans and animals.

Why is it so difficult to warn people about blue-green algae early on?

If there is a specific suspected case, it is possible to determine under a microscope whether cyanobacteria are present. However, additional laboratory analyses are required to determine whether these bacteria also produce toxins at problematic levels. For cyanobacteria that are well known and produce toxins listed in the WHO guidelines (microcystin-LR, anatoxin-a, saxitoxin, cylindrospermopsin), these measurements can be carried out promptly. In the case of lesser-known cyanobacteria that are rare or produce unknown toxins, this can be more challenging and take more time.

Without a specific suspected case, a very dense spatial-temporal network of observation points would be needed to determine the risk of a bloom early on. No such monitoring network exists in Switzerland, and given the resources required, it is unlikely that one will be established in the near future. Few lakes are so well known to local authorities that they can quickly interpret the early signs of cyanobacteria. In most cases, it is not possible to predict the occurrence of dangerous blooms. Eawag is therefore researching and developing automated measurements and intelligent data interpretation models. These may one day serve as an early warning system. This is a promising possibility for cyanobacteria that grow in open water (pelagic blooms). However, it is much more difficult for cyanobacteria that grow on the bottom, sporadically detach and float to the surface (benthic mats).

Interesting facts

- It is believed that cyanobacteria were the first organisms to release oxygen into the Earth's atmosphere through photosynthesis. In doing so, they triggered the development of life as we know it.

- Cyanobacteria are found all over the world, even in extreme environments such as high alpine lakes, deserts, hot springs and the polar regions.

- Lichens, which grow on rocks and trees, consist of fungi and cyanobacteria that live in a mutually beneficial relationship (symbiosis).

- Spirulina tablets are a dietary supplement made from two types of cyanobacteria that do not produce toxins listed by the WHO.