Cyanobacteria / blue-green-algae

Cyanobacteria, also known as blue-green algae, are among the most ancient bacteria on earth and the oldest oxygen-producing life forms on Earth. Naturally present in aquatic ecosystems, they occur worldwide in nearly all water bodies and many moist environments, including in Switzerland. While generally natural components of these systems, some species release harmful toxins (cyanotoxins) that can pose threats to humans and animals. Eawag researchers are therefore studying the ecology of toxic cyanobacteria to better predict their occurrence and improve risk assessments.

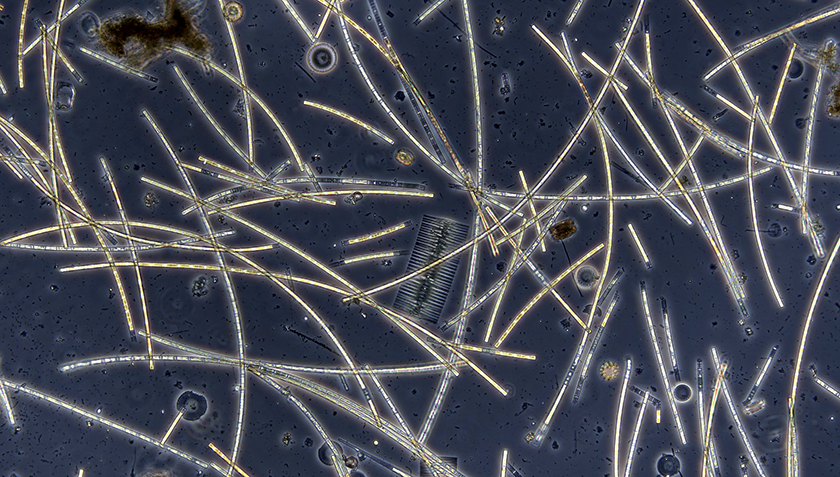

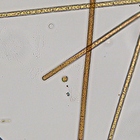

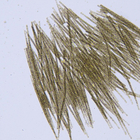

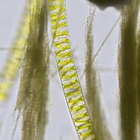

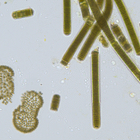

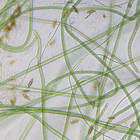

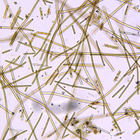

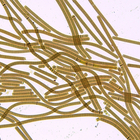

Cyanobacteria are often called blue-green algae because of their colour, which comes from the pigments chlorophyll (green) and phycocyanin (blue) used for photosynthesis. However, depending on the species, they can also be coloured green, yellow, brown or red. For a long time, people thought they were algae, but scientists later discovered that they are actually bacteria — which is why their correct name is cyanobacteria. Specialists often use microscopes to detect cyanobacteria.

Cyanobacteria are one of the first organisms capable of obtaining energy through photosynthesis, thereby releasing the first oxygen into the atmosphere. There are several thousand species of cyanobacteria on Earth, and they are common photosynthetic microorganisms in the oceans and in freshwaters.

To date, around 40 species of cyanobacteria are known to produce toxic metabolites (cyanotoxins). Climate change is increasingly promoting mass proliferation of cyanobacteria – a threat to ecosystems and public health.

Where To Find Cyanobacteria In Surface Waters

Cyanobacteria are classified as pelagic or benthic depending on where they grow in surface waters.

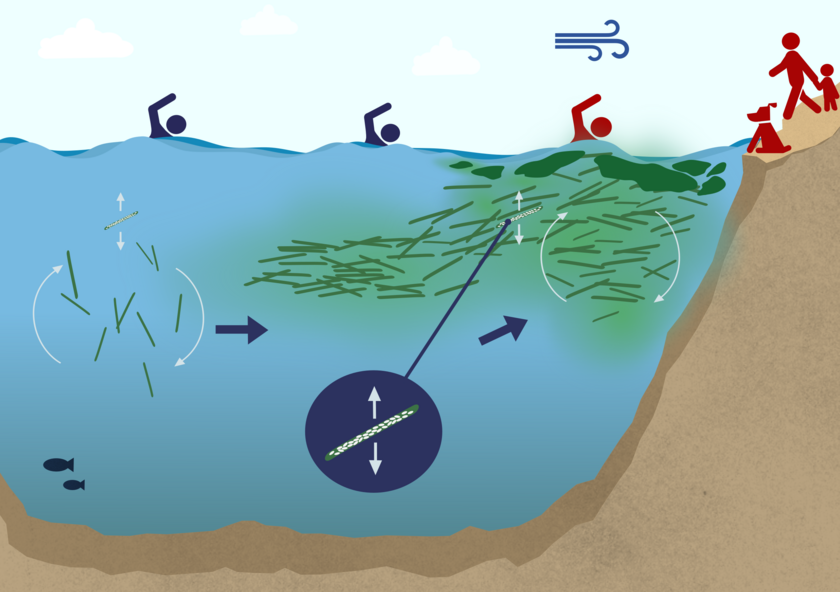

Pelagic Blooms In The Water Column

In open water, the pelagic zone, cyanobacteria can multiply on a massive scale in strong sunlight, with sufficiently warm temperature and nutrients (nitrogen and phosphorus), leading to a «bloom». These blooms float at different depths in lakes and are therefore not always immediately visible. In some cases, cyanobacteria can actively rise to the surface. However, seasonal mixing of the water or strong winds can also passively bring cyanobacteria to the surface. When the biomass floats to the surface, the cyanobacteria are easily recognisable. It is then advisable for humans and animals to avoid contact with them.

Appearance: Cloudiness or blue, green, yellow or red discolouration of the water indicates a high concentration of cyanobacteria. Streaks, foam carpets, flakes or clumps may form.

Occurrence: Cyanobacterial blooms in the water column occur mainly in late summer and autumn, but depending on the species, they can also be visible in winter/spring.

Toxins: The best known and most thoroughly researched class of substances are microcystins, which act as liver toxins (hepatotoxins). These microcystins are produced by many pelagic cyanobacteria.

Danger: There is a particular danger for small children and dogs if they ingest biomass or have prolonged contact with water containing high concentrations of cyanotoxins. This can lead to skin irritation, vomiting, or breathing difficulties.

From left to right: A large part of the previous population remains. Under favourable conditions, a new population can establish itself and grow. Some cyanobacteria have gas bubbles (white circles inside the cyanobacterium), which they use to control their vertical movement in the water column. Due to water temperature profile, currents and wind conditions, the bloom may reach the surface and even the shore. Some of these blooms can release toxins and lead to increased risks for swimmers, small childre,n and dogs (marked in red). (Eawag, Kim Luong)

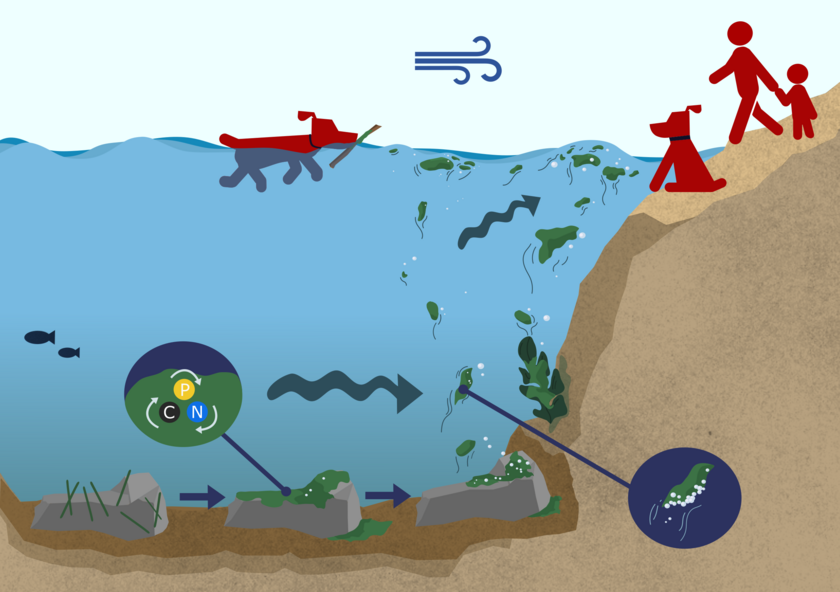

Benthic Mats growing On The Bottom and Floating To The Surface

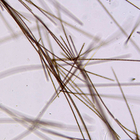

Cyanobacteria grow not only in calm, open waters, but also at the bottom – the benthic zone of rivers, ponds or lakes. There, cyanobacteria form a biofilm on stones, pieces of wood or aquatic plants – benthic mats (also known as «toad skins»).

Unlike blooms in open water, benthic mats can also form when the overlying water is nutrient-poor, clear or only slightly turbid so that sunlight can penetrate to the bottom.

Appearance: These benthic mats can be several millimetres to centimetres thick and often form unnoticed at first on the bottom. Benthic mats appear brown, black or dark green, and air bubbles can sometimes be seen on the surface, which are produced by photosynthesis and contribute to the detachment of mats or fragments from the bottom. The fragments then float to the surface of the water body where they become more apparent. When they dry out on the shore, they often take on a grey or brown colour.

Occurrence: Unlike pelagic blooms, benthic mats also occur in streams and rivers and can cause problems from spring to late autumn.

Toxins: Some benthic cyanobacteria can produce potent neurotoxins, which belong to the class of anatoxins. Anatoxins are believed to be responsible for acute deaths of dogs in Switzerland and worldwide.

Danger: Dogs are attracted by the foul smell of the mats and can ingest toxins when drinking water, gnawing on pieces of wood or licking biomass out of their fur. The concentration of neurotoxins can be very variable and reach toxic levels in benthic mats, even when the concentration in the open water around them is at times barely detectable. Even swallowing small amounts can then be fatal to dogs. Small children may also play with the debris on the shore and accidentally swallow it.

From left to right: Some filaments colonise a surface and attach themselves to it. Under favourable growth conditions, the mat thickens and begins to expand. The mat can detach either due to the production of too many oxygen bubbles or due to hydrological turbulences. The pieces of mat rise to the water surface and can be driven close to the shore by the current or wind.

Increased risks for dogs and small children are marked in red. (Eawag, Kim Luong)

News

News

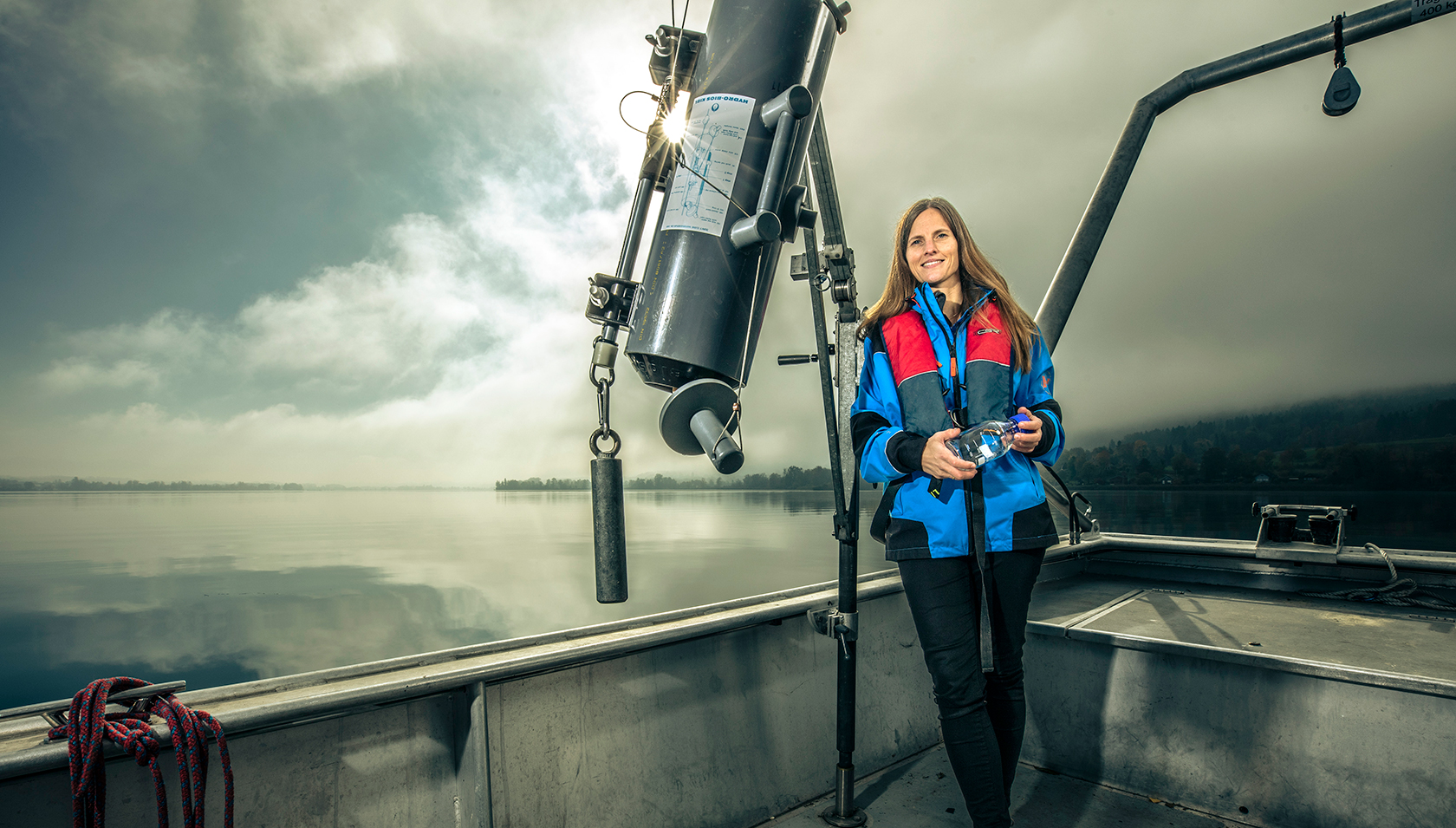

Video: Underwater Drone for Detection of Benthic Cyanobacteria

Our researchers used the BlueROV (Remotely Operated Vehicle) to detect cyanobacterial mats and observe their growth throughout the year. After a successful search, the samples were taken to the laboratory to analyse their potential toxicity.

Aquascope – Live Images From the Underwater Microscope

The underwater microscope adapted for freshwater at Eawag provides images of plankton in near real time (currently from Greifensee and Lake Zug). Immerse yourself in the otherwise hidden miniature world of algae (including cyanobacteria), water fleas, small crustaceans and other creatures: www.aquascope.ch

Research projects

Scientific publications

Cover picture: Bloom of Microcystis sp., Lake Constance (Amt für Wasser und Energie, St. Gallen, Lukas Taxböck).